![DSC_0048 [1600x1200]](http://thelasallian.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/DSC_0048-1600x1200.jpg)

The Supreme Court (SC) ruled last July that three provisions of the Disbursement Acceleration Program (DAP), an undertaking by Philippine President Benigno ‘Noynoy’ Aquino III’s (PNoy) administration, are unconstitutional.

Nevertheless, the administration has fought for the program by filing a motion of reconsideration to the SC. The administration has been defending the legitimacy of the program, especially against persons and groups calling for its abolishment. PNoy was even forced to hold a special address on the DAP last July 14.

DAP for dummies

The controversial DAP was designed to accelerate intrinsic growth by directing savings from idle projects into those that could foster economic growth. As an executive department initiative, Department of Budget and Management (DBM) Secretary Butch Abad was tasked to spearhead the disbursement of P72.11 billion for DAP projects. On Oct. 12, 2011, the first projects under the program were implemented. The initial projects were resettlement programs, training and development modules for government personnel, infrastructure rehabilitation projects, and government building construction and repairs. The DBM has reported that P26 billion-worth of DAP programs have already been started.

Electricity-related projects, rehabilitation of rivers and other national tributaries, financial assistance programs, local government infrastructure programs, and health services, among others amounting to P140.8 billion, were funded by the DAP two years after the creation of the accelerated disbursement program. On Sept. 25, 2013, the DAP was brought into public consciousness when Senator Jinggoy Estrada, in his privilege speech, said that 20 senators received funds from the DAP in exchange for a guilty verdict during the impeachment hearing of former Supreme Court (SC) Chief Justice Renato Corona. Since then, various individuals and groups called for the abolishment of the DAP.

On Sept. 30, 2013, Commission on Audit chair Grace Pulido-Tan announced that her office had begun an investigation on the alleged misuse of the DAP by concerned implementing agencies. The alleged bribe made to the 20 senators was not part of Pulido-Tan’s focus.

The constitutionality of the DAP was first questioned on Oct. 7, 2013, when nine petitions against the further use of the DAP were filed before the SC. On Dec. 28 of the same year, the Office of the President terminated the program saying that it has served its purpose. “Of the DAP releases in 2011 and 2012, only nine percent were disbursed for projects suggested by legislators. The DAP is not theft. Theft is illegal,” PNoy defended in an Oct. 2013 address. No new projects were funded by DAP after its abolishment.

On July 1, 2014, the SC declared that the DAP provisions on the transfer of funds from one branch of the government to another, on the funding of projects not listed in the General Appropriations Act (GAA), and on the creation of savings and withdrawal of funds before the end of the fiscal year, are unconstitutional.

DAP vs. PDAF

Unlike DAP, the Priority Development Assistance Fund (PDAF), or more commonly known as ‘pork barrel’, is a fund that is made available to members of both houses of Congress. By definition, it is used to fund projects in a representative’s district that would not have been funded directly by the national budget.

PNoy took the savings collected from the General Appropriations Act (GAA) and other standby funds, which are approved by the Congress, for the funding of DAP. This enabled the executive department to reallocate funds from existing government projects into other urgent and priority projects.

Both funds have the objective of extending basic services to Filipinos, but the PDAF’s concentration is on the Congress members’ constituents’ needs, while the DAP is concerned with correcting public underspending in order to push for the expected annual economic growth.

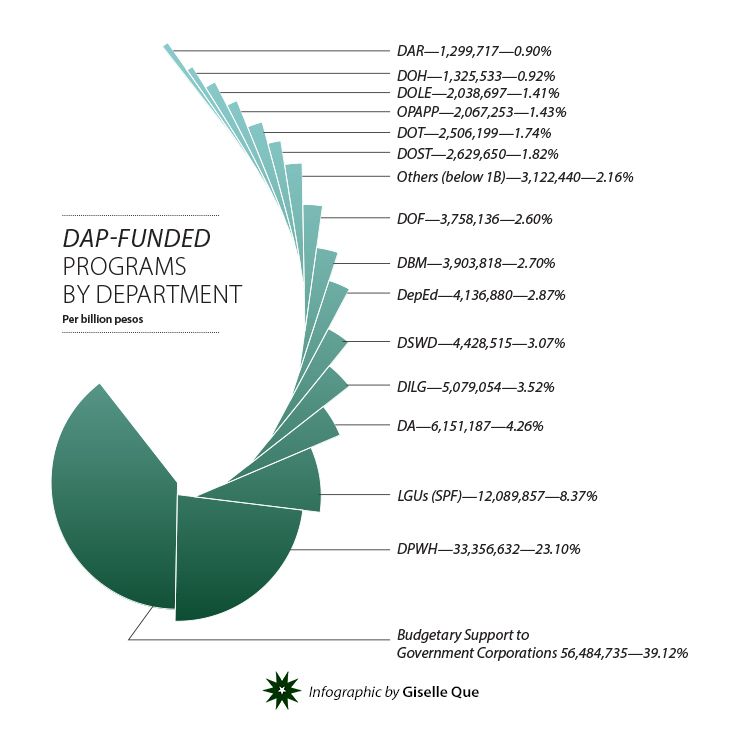

According to the list of DAP projects released by DBM, a total of 116 projects are funded by it. The proposed funding for all of the projects amounted to a little over P167 billion, with P144.378 billion pesos released for their implementation. Starting December 2013, all existing DAP projects were placed on hold. No new project was accommodated under the program.

In addition, DAP projects that have already been implemented, although already declared unconstitutional, can no longer be undone according to the operative fact doctrine. PNoy asked Congress to come up with a supplemental budget to ensure completion of existing DAP projects during his fifth State of the Nation Address.

The other side of the coin

In economics, there are several factors that could affect a country’s economic performance, as measured by its gross domestic product (GDP). Public or government spending is the most common driver of positive economic performance. Usually, spending increases when infrastructure or rehabilitation projects are entered into by the government. During PNoy’s first year, he was unable to meet his administration’s growth project since his predecessor, former Philippine President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo supposedly used up most of the 2010 budget even before the change in administration.

PNoy and his cabinet members had to resort to diverting savings into selected projects to augment the difference between the actual performance of the economy and the projected result. Infrastructure and rehabilitation projects were financed by the DAP; the inclusion of other projects under the program was geared towards accelerating public spending to boost economic growth.

Gerry Eusebio, a professor from DLSU’s Political Science department, explains that DAP is “A fast-tracking of financial infusion to different areas of development, in order to pursue economic development.” Proof to this is the continuous economic growth since 2012, a year after DAP introduction, of which the Aquino administration prides.

“The problem is the way the disbursement was conducted. (It) was not in the ordinary sense or in the legal sense of disbursing money,” Eusebio adds, pointing out to the flaw of the administration’s program. The professor believes that the DAP was created in good faith. Eusebio even says that it has opened job opportunities especially in infrastructure development, but he reiterates that the means of the government contrasts to what is legally right. He also sees that the implementation of DAP was offhand and it could have undergone more consultations.

While the SC is still in the process of deciding whether to grant the motion of reconsideration, Malacañang has taken steps to educate the public on DAP. According to Alexandra Suplido, a member of the Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office, the Aquino administration has been transparent about defending the disbursement program, especially to media.

Suplido highlights that her office respects that “as independent institutions, the media is free to report in a way that they want… [even if] the way the media decides to showcase DAP is not to our [office’s] liking.” She also reminds that the government has a feedback mechanism where concerned citizens could relay their concerns and questions about any government issue, especially on DAP.

Two impeachment complaints were filed against PNoy, in light of the SC’s ruling over the constitutionality of the DAP. The House of Representatives Committee on Justice junked all complaints in a public hearing held last Sept. 2, 2014.

17 replies on “Politics aside, DAP explained”

.

ñïàñèáî çà èíôó!

.

thanks!!

.

thanks.

ccn2785xdnwdc5bwedsj4wsndb

[…]Sites of interest we’ve a link to[…]

xcmwnv54ec8tnv5cev5jfdcnv5

[…]Here is an excellent Blog You may Uncover Intriguing that we Encourage You[…]

Title

[…]just beneath, are quite a few entirely not related sites to ours, nonetheless, they’re surely really worth going over[…]

Title

[…]we like to honor many other internet internet sites on the internet, even when they aren’t linked to us, by linking to them. Under are some webpages really worth checking out[…]

Title

[…]one of our visitors not too long ago suggested the following website[…]

Title

[…]we prefer to honor lots of other online web pages around the net, even though they aren’t linked to us, by linking to them. Underneath are some webpages worth checking out[…]

Title

[…]here are some hyperlinks to internet sites that we link to for the reason that we feel they’re worth visiting[…]

Title

[…]we like to honor quite a few other net websites on the web, even though they aren’t linked to us, by linking to them. Below are some webpages really worth checking out[…]

Title

[…]Wonderful story, reckoned we could combine a couple of unrelated information, nevertheless seriously really worth taking a look, whoa did one particular study about Mid East has got a lot more problerms at the same time […]

Title

[…]although web sites we backlink to below are considerably not associated to ours, we feel they’re truly worth a go by means of, so have a look[…]

Title

[…]below you’ll obtain the link to some websites that we believe you need to visit[…]

Title

[…]just beneath, are numerous entirely not related web pages to ours, nevertheless, they may be surely really worth going over[…]

Title

[…]Every as soon as in a when we decide on blogs that we study. Listed below are the newest web sites that we select […]

Dreary Day

It was a dreary day here today, so I just took to messing around on the internet and realized