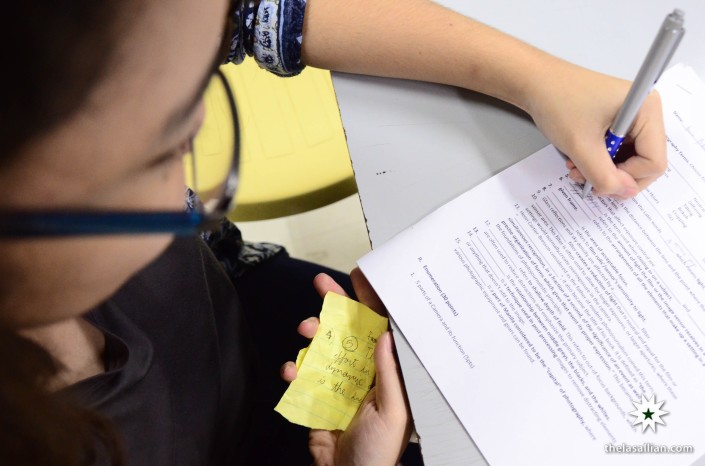

The Student Discipline and Formation Office (SDFO) reports the largest number of cheating cases filed against groups this year, with the total number of students filed cheating against exceeding the total of last year’s cases.

The SDFO reports that as of this year, three cases with a large number of complainants are currently being processed: a case from 2011 involving 17 students in the School of Economics, a case from 2012 with students from the College of Science, and this year, with 16 students accused of academic dishonesty and conduct unbecoming of Lasallians. As of press time, the 2011 case has already been decided, while the case from 2012 is still pending a decision. The case from this year is still pending hearings, the next of which will be during the last week of November.

An official spokesperson from the SDFO shares with The LaSallian that for the second term, the bulk of cheating cases filed are still being processed. “Dahil sobrang dami nila, kailangan silang i-schedule pa [Because of their number, most of them have yet to be scheduled],” states the SDFO. “Kapag ang [Student Discipline Formation Board] kasi napasahan ng case, it doesn’t mean na may decision na sila agad, and it doesn’t mean these will be processed immediately. Minsan medyo matagal yung proseso nila [When a case is brought up to the Board, it doesn’t mean they’ll come up with a decision right away. The process really takes a while].“

The ground for cheating

Cheating or academic dishonesty is an implicit offense against the standards followed by academic institutions. Section 4.13 of the Student Handbook states that “a student’s academic requirements, such as assignments, term papers, computer programs and projects, and thesis papers should be his or her own work. He must distinguish between his or her own ideas and those of other authors.”

The student must cite references, direct quotes, and other sources (including data obtained from tables, illustrations, figures, pictures, images and video) following the prescribed format of the discipline. Failure to do so would be ground sufficient for the charge of academic dishonesty.

Dante Leoncini, President of the Faculty Association and a regular member of the SDFB shares that this year has seen the proceeding of a case with the largest number of complainants during his time as a member of the SDFB, although he does not reject the notion that there may have been bigger cases prior to his term.

Leoncini says that allegations of cheating filed by professors must first pass through the Board before the SDFO can begin their investigations of the case. After this, the SDFO says that the investigation and collection of evidence such as test papers and interviews by its Enforcement section ideally takes a maximum of one week.

After the investigation, the complainant professor is asked to explain orally and in writing why the case was filed, and it is after this the case report is made by the SDFO and submitted to the University Legal Counsel for review and further scrutiny. The Legal Counsel either dismisses the report in the occasion that no case is found, or given clearance for the case proceedings to push through.

The procedure that follows depends on the degree of the student’s admission of guilt. If the student fully admits to cheating, then the University Panel for Case Conference (UPCC), where a panel of board members discuss with the student and the student’s parents on how the student can improve, but the repercussions of the offense and the grade are implemented fully. Partial admission or denial involves a few clarification questions in summary proceedings; a full defense of not guilty entails a formal hearing, where students are allowed just representation in the form of private lawyers.

Cheating, accomplices and collaboration

Alleged mass cheating is not a case unique to the University, as even in prestigious international universities the phenomenon of cheating is a condition that is difficult to curb. Last year, Harvard University filed sanctions against 60 students in a cheating scandal that implicated as many as 125 students in the class “Introduction to Congress”. One of the difficulties with said case was the professor inviting students to openly “collaborate” with each other prior to the examination where the proven cheating took place. The Harvard students who received the sanction were forced to withdraw from school from two to four terms.

The same numbers may be present in La Salle, where professors may file against entire classes. The SDFO reports that in one of the cases currently pending a decision, 17 students were pinpointed out 40 students who were all implicated with cheating. “If you check the handbook,” reports the SDFO spokesperson, “Cheater ka kung aware ka pero wala kang ginawa. Yung sa case ni ito, nadismiss yung ibang mga case. Hindi siya madalas na nangyayari, pero nangyayari siya. [You are still an accomplice even if you don’t do anything but are aware of cheating. In this case, some charges were dismissed. It happens, but not all the time.”]

Scholarly research has shown that one of the prime difficulties with cheating is the ambiguity between cheating and collaboration. A 2012 article by The Chronicle of Higher Education reports the results of a study conducted in Duke University, where students were shown to think that “the inappropriateness of unauthorized collaboration varies and that working together is valuable to the learning process.” Copying was perceived to be “taking no effort”, while collaboration implied “active engagement with the material.”

Dr. Donald McCabe from Rutgers State University conducted a study on academic dishonesty revealing that as group norms “lead to high levels of cohesiveness and loyalty, team members become less likely to police teammates’ unethical behavior or report it.” Based on the study’s values surveys, students in departments and in institutions with high mean scores in team orientation don’t score as high on accountability and risk-taking.

Recommendation: seminars, remove lawyers

The University has started a series of sessions titled “Cheating: I Know It When I See It, But Prove It” for faculty members, conducted by former University Legal Counsel Atty. Sales, where he shares experiences from hearings, and gives tips on how to pinpoint cheating, produce good evidence, properly defend during hearings, among others. The SDFO is for this behavior: “For some teachers, it’s enough to give them a 0.0. Hindi na sila nagfifile [They do not proceed to file a case]. Kaya nga we are really encouraging teachers to not just give 0.0 but to give these students proper formation by filing the cases.”

The SDFO also wishes to create a Professional Learning Community against cheating, gathering all teachers with experiences about academic dishonesty in a venue to discuss it. Faculty members who have filed complaints, together with two faculty members per college, will be gathered for a discussion on cheating methods, past cases and advice. The SDFO is expecting to hold the PLC before the end of the second term.

As a policy recommendation, the SDFO seeks to discourage the presence of lawyers in group cheating cases, minimizing the number to at most one lawyer for the entire group. Individual lawyers appointed to serve as the counsel of individually implicated students would be permitted to review the case and coach students beforehand, but may not speak during the hearing. This is because the office believes that the presence of multiple lawyers delays the case processes.

“Tumatagal yung mga cases na to kasi nagpapasok ng maraming tao, maraming nagtetestify for or against [The cases drag on because a lot of people are dragged into it, there are a lot who are called to testify for or against],” shares the SDFO’s spokesperson. “[What stalls the process] is the presence of lawyers, and it voids the function and thrust of the Student Discipline Formation Board to make formative decisions.”

Another recommendation is to present, based on the accounts of faculty member, common themes and scenarios identified and compiled into a paper or report, to be forwarded to the rest of the academic community. This may be shown during faculty orientations to serve as a guide to prevent cheating, although the SDFO admits that this is not the easiest value to instill. “For students, it’s really very hard to prevent (cheating)… Because it is difficult to touch on the way they have been formed at home and in their previous schools.”

3 replies on “SDFO reports difficulties, increase in cheating”

.

tnx for info!

.

hello!

.

tnx!