It all started with an assignment in second grade.

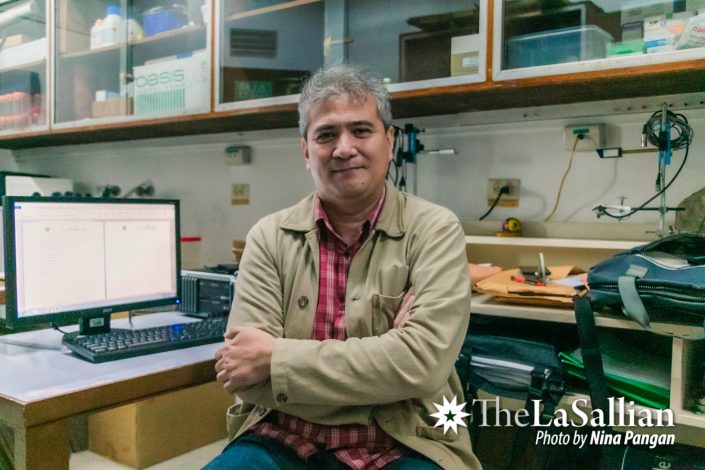

“Which would dry faster, black clothes or white clothes?” recalls Joel Chavez, an associate professor and lecturer from the Biology Department of DLSU.

Submitting the wrong answer, his teacher would later on explain the proper process of how heat transfers from one medium to another, consequently serving as the catalyst to Chavez’s deep interest in the scientific field. He reveals that science gave him the opportunity to think about possible solutions to problems humans could encounter on a daily basis. “I love the way it makes me free to think,” he enthuses.

A ‘turning point’

Chavez recounts his enjoyment of spending time in the laboratory during his undergraduate days. He would often find himself using the facilities immediately after his 4 pm classes, staying there for hours on end—sometimes reaching even 12 hours. This would later go on to be a frequent habit of his, rarely feeling worn out and instead enjoying the process of hypothesizing and tweaking solutions until he found the outcome he needed. This, he discloses, served as the “turning point” to his long stay in the field of science.

Although his original plan was to become a medical doctor, he shares, “I realized I love doing science more [so] I left [medical] school and then I started my career in the academe.”

He reminisces that he has been in the educational sector for 25 years, with 10 of those being spent in the academe, and the rest working for the government. Chavez’s time in the government allowed him to draft policies that set the standards for higher education’s science programs. The opportunity allowed him to “infuse” his ideas into the policies that lobbied for science in the education sector.

He recalls, “I would share with [government agencies] my own ideas about how I see how science can be improved in the classroom, how training for students can be done.”

Career paths

“A lot of people don’t think there’s a career in science,” Chavez asserts. While there are professions such as medicine and pharmaceuticals that may be highly regarded in that field, he claims that disciplines such as biology or physics may not share the same sentiments.

He surmises, “If you don’t go into a professional track, then anong gagawin mo as a physicist?”

(Then what will you do as a physicist?)

He claims that, compared to other countries, the Philippines has no clear way to track the statistics related to one’s own profession. Additionally, he cites that the country is also lacking in research institutes or employable companies that have research departments. All the while, there is the factor of students fearing that if they choose a profession in the field of science, the only possible option for them career-wise would be to join the academe.

Admitting that while the problem does exist, Chavez proposes that the solution may not be focusing on where you could go to do activities in science, but “how you use your training in doing science.”

He explains that there is a myriad of traits and learnings one can pick up in different fields of science and apply it to other disciplines, such as business. He reasons, “Kasi [science] teaches you how to think logically; it teaches you how to search for explanations; draw up your own experiments; analyze your own results.”

Reinventing tradition

Chavez observes that the educational system in the country is “very traditional”, with a classroom setting where students spend would spend three hours a week or 54 hours per semester for one course.

Sticking with the current arrangement of educational institutions, Chavez supposes that the setting may not be able to afford long training sessions for students. This could also result in them possibly failing to appreciate the discipline of their choice as they do not have the luxury of time to understand and study the subject at their own pace.

“Sitting, for example, [for] one and a half hours in the classroom—would students have that deep inclination to be actually be involved in what it is that [professors] say?“ he questions.

Moreover, he emphasizes the importance of the potential for students to simultaneously learn and love elements in their discipline. He states that one of the conundrums teachers face right now would be enticing students to pursue science careers and cultivate the same appreciation he has for the discipline.

Once a very passionate student who yearned for scientific discovery, Chavez believes that students need more than what the current educational system can offer. He compares this to how he spends more hours on his field of expertise than what the current educational system provides students, emphasizing the need for them to take the initiative and spend more time exploring their respective fields of science to learn. He urges, “Let’s do away with a lot of standards.”

Like any other scientist, he advocates a change in ordinary practices and welcomes reinvention.

A question is asked by their teacher: “Which would dry faster, black clothes or white clothes?”

Given the proper time, materials, and guidance to conduct the experiment properly, they begin to assess the problem posed.

Minutes later, as a student gains the courage to raise their hand, the correct answer emerges—and a love for science is born.