In the year 2000, the Philippines breathed a sigh of relief as the World Health Organization (WHO) delivered the good news and declared the country polio-free. The country, at that time, had not had a documented case of polio for seven years.

That all changed this year when the Department of Health (DOH) confirmed two cases of polio within the country just days apart; one from a three year old girl in Lanao del Sur on September 19 and another from a five year old boy in Laguna the very next day.

Meanwhile, samples of sewage water from Manila and Davao have also been found to carry poliovirus—the causative agent of polio which resulted in the aforementioned cases.

Consequently, the DOH has declared a polio epidemic within the Philippines. While two cases may seem too few to merit a reaction at all, even a single reported case of vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (VDPV2) is considered an epidemic for what was previously called a “polio-free” country.

Poliomyelitis, also known as polio, is an infectious disease that targets the brain and spinal cord, leaving its victims permanently paralyzed. The recent Philippine cases were caused by the VDPV2 strain, which arose from a mutated form of the polio vaccine. The vaccine contains weakened and supposedly non-harmful forms of three types of wild or naturally-occurring polioviruses.

Yet the question does not lie on how the virus works, but rather on how it spread in the first place: it was revealed by the WHO that VDPV2 only emerges in areas with low immunization coverage and poor sanitation. It is under these conditions that the weakened virus can be passed to non-vaccinated people, mutating into VDPV2 and becoming harmful.

Earlier this year, the WHO reported that the Philippines climbed to third place among countries with the most measles cases over the span of 12 months with 45,847 documented cases. The DOH explained that measles, a respiratory infection that results in skin rashes and high fever, had been spreading in the country due to vaccine hesitancy, among other things. The organization also revealed that 66 percent of reported deaths from measles cases had no prior history of being vaccinated against measles.

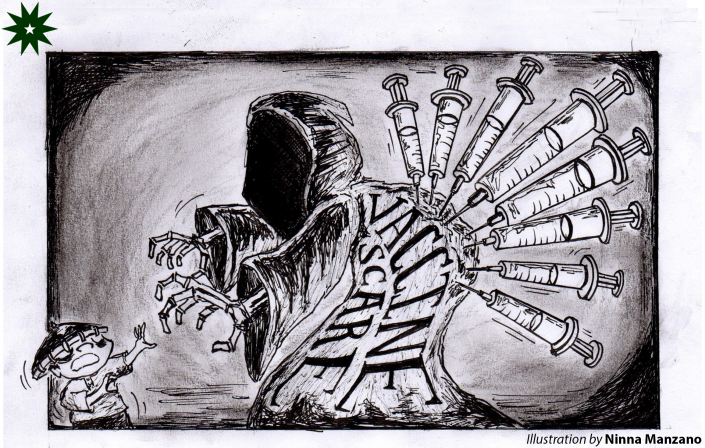

After the Dengvaxia controversy, researchers from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine found that among their Filipino respondents, trust in the safety of vaccines plummeted to 21 percent in 2018 compared to the 82 percent trust rating from 2015—three years before the Dengvaxia controversy. Reports had surfaced with claims that children allegedly died due to complications after receiving the dengue vaccine. This greatly affected public perception on vaccination as a whole, despite health professionals contending that deaths linked to Dengvaxia had not necessarily been due to the vaccine.

With some communities having less vaccination coverage than others, viral diseases such as polio have been found to be more likely to mutate and propagate in unimmunized communities since the immune systems of their residents are ill-equipped to respond to these specific diseases. However, greater vaccine coverage, at the very least, slows down the spread of the virus and lowers the chances of infection among the unvaccinated.

With the immunization coverage of both polio and measles in the Philippines dropping to less than 70 percent, as opposed to the targeted 95 percent, it may be easy for health officials to present their data and say the solution would be to get vaccinated. However, public trust still plays a vital role in all of this.

While there are many factors that contributed to the incidents mentioned above, we cannot discount the harmful impact of the mistrust and hesitancy toward vaccines. Misinformation, compounded by lack of accessibility to health services in some remote locales, makes regaining public trust in health care difficult.

It will be a journey that necessitates the clearing up of misinformation, ensuring the correct usage of vaccines, and making vaccines and other necessary health services more accessible before the trust in these interventions can be revived.