The relationship between the Philippines and the United States (US) has historically been considered one of America’s strongest bilateral ties in the world. Some 78 percent of Filipinos still view the US in a positive light, a survey conducted by the Pew Research Center found in 2017. But this relationship is under threat as Filipino government officials have recently tried to hit back at the US over the passing of the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act, also known as the Global Magnitsky Act.

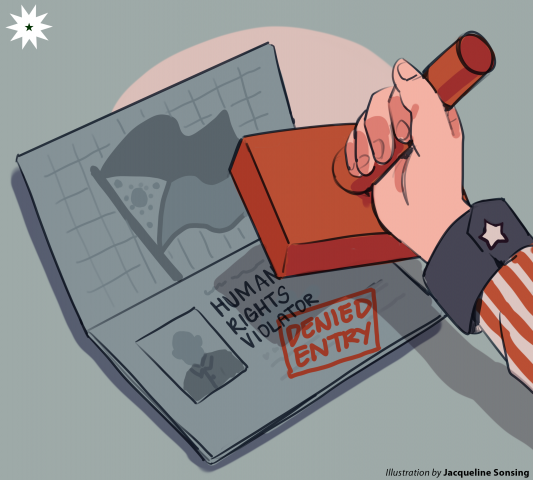

Outrage erupted in Malacañang last December when news broke that the 2020 US budget, signed into law by US President Donald Trump, contained provisions empowering the Global Magnitsky Act—denying US entry for Filipino government officials complicit in the jailing of Sen. Leila de Lima. The law would also freeze any US-based assets held by these officials.

In defense of human rights

The original version of the controversial measure, then known as the Magnitsky Act, was signed into law in 2012 by then US President Barack Obama. It was intended to punish Russian officials involved in the imprisonment of Russian tax accountant and whistleblower Sergei Magnitsky, who was arrested for revealing extensive corrupt practices among Russian government officials. Magnitsky was mistreated in prison and he would eventually be beaten to death.

With the Magnitsky Act, the US was able to freeze the US-based assets of the Russian officials involved, and ban them from entering America entirely.

In 2016, the US Congress approved a dramatic expansion of the law—now called the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act—which allows the US government to apply similar sanctions against government officials of any country who have committed supposed human rights abuses. Since then, the list of sanctioned persons grew to cover Saudi officials involved in the brutal murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, and military officers tied to the persecution of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar.

In April, US legislators filed Resolution 142, which would also sanction Filipino government officials who helped imprison De Lima. The senator, who has been detained for almost three years over “trumped-up” illegal drug charges, named a number of government personalities as responsible for her arrest, among them President Rodrigo Duterte and Presidential spokesperson Salvador Panelo.

Dr. Alejandro Soler, an International Relations specialist and Associate Professor in the University’s International Studies Department, favorably compares the targeted approach of the Global Magnitsky Act against country-wide sanctions. “Targeting individuals zeroes in on people involved in alleged crimes or violations. It spares the vast majority of the population that has nothing to do with the alleged violations,” he explains. He cites that the economic embargoes imposed on Iran and Cuba had adversely impacted people who did not play a part in the reasons for the sanction. “At the very least, it shames alleged violators of human rights,” Soler says.

Government reaction

Faced with the possibility of a US travel ban, Philipine government officials condemned the law. In a statement last January, Panelo blasted the measure as “misguided” and “bullying”, blaming the “bogus narratives of President Duterte’s usual antagonists”.

Cabinet Secretary Karlo Nograles also lambasted the supposed intrusion on Philippine sovereignty, saying, “Parang dinidiktahan tayo sa kung paano patakbuhin ang justice system natin. Independent tayo. Sovereign state tayo.”

(It is as if we’re being instructed on how to run our own justice system. We are independent. We are a sovereign state.)

Soler disagrees. The law, he explains, is “an exercise of US power”, rather than an infringement of sovereignty. “The aim of the US is clearly policy change, and it feels it can achieve this by exerting its influence on other countries to align their policies with the principles the US adheres to,” Soler explains.

Three of the bill’s proponents, US senators Edward Markey, Richard Durbin, and Patrick Leahy, have also been banned from entering the Philippines. Panelo threatened to revoke the visa-upon-arrival privilege for American citizens, which would force them to instead acquire regular visas before visiting the country.

“President Duterte is sorely mistaken if he thinks he can silence my voice and that of my colleagues,” responded Markey in a statement last January.

From the ground

Soler discredits Panelo’s threat, saying that the recent counter-threat to impose visa requirements on American citizens would only serve to “complicate US-Philippine relations” and prove ineffective in reversing the sanctions.

But he admits that the

Global Magnitsky Act might not be enough to force a shift in domestic policy in

the Philippines. “The current administration seems steadfast in its belief in

its actions, he stresses. “It has time and again dismissed calls from the

international community to be more transparent in its campaign against drugs

and refuted accusations of human rights abuses.” Soler adds that the policy

might serve as a “platform” for the Duterte administration to label its critics

as “enemies of

the state”.

Soler additionally warns that previous sanctions by the US to other countries have historically “mostly only worsened” tensions between the US and the sanctioned state. In the same breath, he mentions that Filipino officials would find the US sanctions “very difficult to circumvent.”

The European Union (EU) has also begun working on its own version of the law, which would likewise freeze the EU-based assets of human rights offenders and ban their entry into the EU.

By the end of January, relations have only soured further. Duterte angrily threatened to cancel the country’s Visiting Forces Agreement with America after former police chief and incumbent Sen. Ronaldo dela Rosa confirmed last January 22 that his US visa had been cancelled. The cancellation is reportedly due to the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act, which also allows visa bans against foreign officials tagged as human rights violators. The President has also rejected an invitation to attend a special summit in the US next March and has more recently forbidden members of the cabinet from traveling to America “indefinitely”. The lines are being drawn in the sand.

Update: February 13, 2020, 5 pm

As of February 13, Duterte has ordered the cancellation of the VFA, despite protests from Filipino officials.