Back in 2017, The LaSallian spearheaded a campus journalism seminar, PressPlay, which focused on the credibility and reliability of news reporting—especially from outlets like Philippine Daily Inquirer and ABS-CBN who, despite being impartial, were labelled as “biased media” by President Rodrigo Duterte. At the time, news coverage on his administration’s Drug War, whose effects on Filipino society are still apparent today, peaked.

Three years later, Duterte has threatened to shut down ABS-CBN due to the network’s failure to air his campaign advertisements for the 2016 presidential elections. The verbal threat became a tangible one when Solicitor General Jose Calida filed a quo warranto petition to the Supreme Court earlier this month, claiming that the media company had abused its franchise. It was only after an apology addressed to the President was issued in a Senate hearing last February 24 that Duterte forgave the company, stopping just short of taking a side on the franchise renewal concern. The quo warranto thus remains unresolved, with the high court scheduled to hear the case on March 10.

ABS-CBN’s case is only one of the many instances where Philippine media has faced threats in recent years. Time and again, both the press and the media have been lambasted and criticized for how they craft the narratives of the news. The supposed bias that journalists have in reporting seems to stem from the manner of presentation; the way the news is reported suggests that some form of stand is made or a side is taken while presenting the truth.

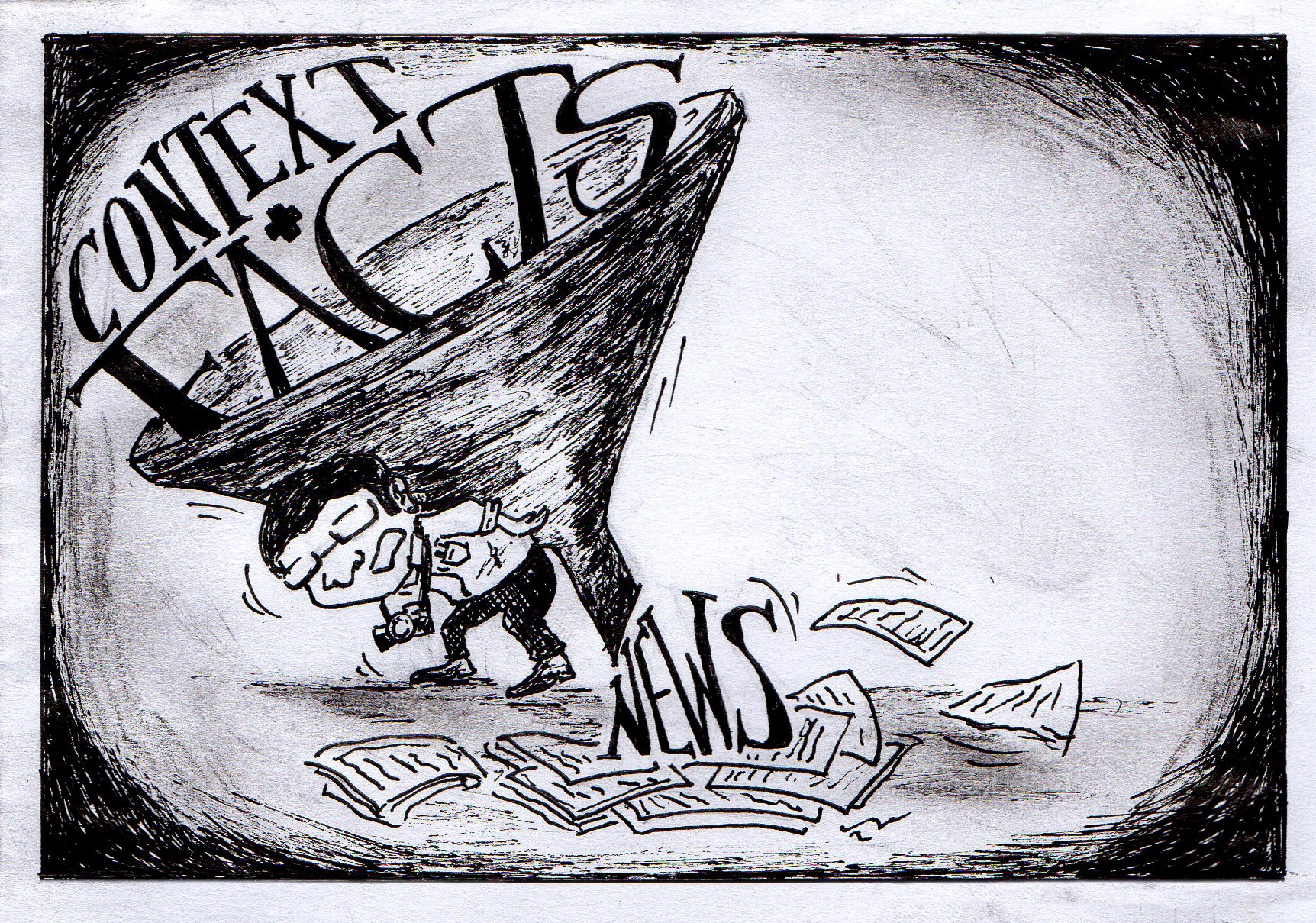

It is true that the media is obligated to present the truth to its constituents, employing rigorous fact-checking and verification to ensure reportage is accurate, timely, and comprehensive. But the media’s role as a truth-seeker and truth-teller is not a passive retelling of information, mediating from the source to the audience; instead, it takes on an active role in choosing, cutting, and contextualizing content.

When a story arrives in their hands, journalists make the call to consider it newsworthy or not—in other words, to what extent the item should be reported—and thereby dictating how frequently and prominently a story is told. After determining what to report, journalists must determine how to report it; constrained by word count and airtime, they must direct the story’s angle to not only cover all the essential details but also to ensure that it is told in a compelling manner.

In disseminating the truth to their audience, journalists do not simply list facts, but they discern and synthesize the information they gather. Facts on their own lack meaning without context, which journalists should crucially provide, as only by doing so would a clearer picture of the issue be presented.

It is also not to say that skepticism toward the media is unmerited; questioning what you are told signals an attempt to seek out a deeper understanding of the issue and can bring about meaningful discourse, something that the media should allow to thrive. It only becomes counterintuitive when the same skepticism leads to distrust, dismissing at face value any information or perspective that runs counter to one’s personal worldview.

Beyond commitment to the process of developing and putting out news is the perceived obligation and mission to abide by the 10 so-called pillars of journalism—core tenets that every journalist should follow—particularly the obligation to the truth. If others were to wrongly contextualize this obligation, then it could be misinterpreted that journalists can freely choose to be biased toward something that can arguably be relative. Without a solemn commitment to journalism’s pillars, a media practitioner risks treading the path of a gossipist or a propagandist, who sets aside what is true in favor of an unfounded judgement or a foreign loyalty.

However, when this commitment becomes ingrained in the nature of a journalist, the truth no longer represents an objective toward absolute neutrality. Instead, the truth becomes the guiding principle of the press who is accountable to its major stakeholders: the citizenry. Very much so, at least in the context of the Lasallian community, The LaSallian commits to be biased toward the truth, a virtue it teaches to its editors, staff, and readers.

For the press, there will always be emphasis placed on finding a critical balance between angling news reportage and abiding by the principles of responsible journalism without compromising the truth and twisting reality. The public and society need to know the truth and the information that journalists are privy to—even if that truth is often a tough pill to swallow.