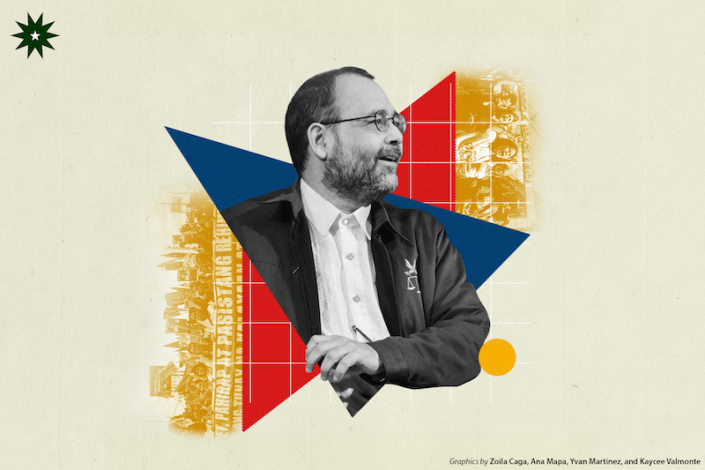

Jose Luis Martin Gascon, or Chito as they call him, was an intimidating yet warm man. Even through the barrier of a computer screen, his eyes are focused, a window into his own sharp intellect.

Having served as the chair of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), he must have always been ready to speak up for those who could not defend themselves while simultaneously fending off attacks from those who are meant to support him. But, as Gascon says wryly, “If you can’t take the heat, get out of the kitchen.”

In an interview last August, The LaSallian sat down with Gascon to discuss how CHR deals with the Duterte administration and his would-have-been future plans.

For those unfamiliar with the CHR, what role does the Commission play?

The Commission on Human Rights is [part of] the global narrative [of] institutions of [the] government…that perform the role of advocating, promoting, and protecting human rights. You can think of CHR as a constitutional office—established by the 1987 Constitution—to protect against the worst abuses of human rights by promoting human rights.

Whenever we see violations of those rights…we investigate and we report, call out, and make recommendations. Our mantra in all of this, aside from human rights standards…is very simple: the dignity of all.

As part of the youth, you had contributed to nation building and were the youngest person on the 1987 Constitution Commission as well as in the country’s Eighth Congress. Reflecting on this, what role do you think the youth plays in shaping modern Filipino society?

I was fortunate to have been an active youth leader…involved in the transition from dictatorship during Marcos to democracy with the [1986] People Power Revolution with the assumption to office of Cory Aquino. I was a product of that history.

What we wanted in the post-dictatorship period was acknowledgment [and] recognition of the voice of young people. Young people should be empowered and enabled…My call is that the youth of today must be involved in public affairs; understand and appreciate that they have these rights; and enjoy and exercise these rights because these are guaranteed to you by our democratic system.

As one of President Rodrigo Duterte’s biggest critics, making you one of his constant targets, what fuels you in standing up for what you believe is right despite the tirade of criticism?

I need to clarify—I don’t really consider myself as a principal critic of the President or his administration. My role…is primarily to serve the Constitution and the people by affirming the fundamental rights that are already guaranteed by our fundamental law. I don’t criticize or become a critic because I want to, but rather because I have to—because it’s my duty. Walang personalan, trabaho lang.

(Nothing personal, just work.)

Since my youth, I’ve been fighting a dictator, and I’m always prepared up to my last day here…to continue to fight for the same principles that were molded when I was a young person.

In my case, one thing that keeps me moving and drives me is my daughter. I experienced martial law and dictatorship—no freedom, democracy, [or] human rights. I will not wish that on my daughter or the next generation. I will only hope that tomorrow is better than today or yesterday.

Throughout your term, there have been criticisms that your partisanship and allegiance to the Liberal Party have affected your impartiality as Chair. What are your comments on this?

My record is clear and transparent. Nothing is hidden. What I have fought for during my youth, my activism against the dictatorship, are the same things I fight for up to today. The only difference is I’m given responsibilities. And since I assumed my responsibility as Chair, I have made sure in all my professional and public service undertakings…that we do so in accordance with the law.

When I step down, I think I will continue my activism and that may involve returning to some form of partisan activity. But…in my oath as Chair…I have done everything I can to ensure that we do things in accordance with our mandate.

Having also done government work during previous presidential administrations, what would you say sets Duterte apart from the previous presidents of the Philippines?

I would say that the Duterte leadership archetype is much more akin to the Marcos leadership archetype—the authoritarian approach to doing things…instructions being given down using populist rhetoric…But in terms of outcomes and results, the situation of the great majority remains the same.

The constitution established in that period remains the constitution upon which the current administration was elected. But, sadly, I have to say that the Constitution is only affirmed and respected in rhetoric, but not in practice. Duterte’s authoritarian form of leadership lends itself to regular abuse and violation of the Constitution.

During his final State of the Nation Address, Duterte issued shoot-to-kill orders and failed to mention prevalent human rights issues. What are your thoughts on this?

I think he merely reiterated what he was actually saying from when he was campaigning…this language that normalizes violence. It was dangerous when he was saying it as candidate Duterte, it [is] dangerous when he became president and continued to say that.

The killings have continued perhaps not at the same scale and pace as they were in the first six months—you don’t see reports of the violence on our front page anymore…We have shrugged our shoulders and accepted that that is a matter of policy when it shouldn’t be. Violence should never be public policy. That language is corrosive language, it undermines the rule of law.

It’s been a difficult period in the Commission…trying to prevent the worst forms of violations to occur with minimal success. But essentially, we just have to navigate the terrain…[we’ve] learned to accept that so long as this is the current Constitution and we are in charge of this Commission, we will perform our mandate this way. And while maybe there’s some degree of grudge…we have moved along.

The Philippines recently made an agreement with the United Nations (UN) to establish a three-year program on human rights. What is the involvement of the CHR in this and what hopes do you have for the program?

The CHR is part of the steering committee. We’ll work with the government, the UN, [and] civil society to make sure that the indicators and components of this three-year Human Rights Action Program are implemented as best we can.

When the resolution was made in Geneva last year…to institutionalize this program [in 2022], we welcomed it. We said, “What’s important is not just what is agreed upon in Geneva, but ultimately…[the] improvement of the conditions on the ground.” We are looking at this very carefully, and we will monitor and report on whether it has resulted in improvements on the ground…We believe in the sincerity of both…DFA (Department of Foreign Affairs) and DOJ (Department of Justice) who have manifested their commitment to implement this program, and we will support it as best we can.

Last June, the International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor announced that they will be conducting investigations on the Philippines’ “war on drugs”. Even with the Supreme Court’s affirmation of our need to cooperate, it is no secret that Duterte does not want to participate. What is your take on this situation?

There will be difficulties because the Philippines was a member of the ICC, but we withdrew. The current administration will probably not cooperate with the conduct of that investigation. Nonetheless, the ICC has continued its work at the preliminary examination stage and, once authorized, will continue with its investigation in the end once it’s allowed to do so.

Of course, it’s best if the Philippine government cooperates and we urge the Philippine government to cooperate with the ICC. But if he (Duterte) chooses not to, that will be part of the record.

We have not been requested from the ICC formally for cooperation, but should we be requested, we’re ready, willing, and able to cooperate as best we can.

What accomplishments of the Commission during your term are you proudest of?

I’m very fortunate to have been given this opportunity [of becoming its chair]. When I assumed my responsibilities in 2015, what I promised myself was to make sure that when I [would] step down…I would turn it over to the next set of commissioners in a far better place than when I had received it. I would be most proud to see that the Commission has grown from strength to strength to strength, building upon what we started before me and continuing from where we leave off. As part of that, one of the things that I really wanted to highlight in my mandate was to ensure that the CHR becomes a safe, enabling, and empowering space for the human rights community.

With your term as CHR Chairperson ending next year, what are you planning to do after?

As long as I still have energy…I will continue to dedicate myself to this work—being an active participant in the strengthening of democratic institutions.

I studied law. I’m a lawyer…but I don’t see myself as a practicing lawyer. I’ve been a teacher and I hope to continue teaching.

What I hope to do when I step down is to leverage my experience, my knowledge…to assist the next generation as well as other actors—whether in government and non-government, in political parties, both nationally and internationally. I also have a space of engagement at an international level, because there are many challenges to human rights and democracy.

So long as may buhay at may lakas, iaalay ko [ang sarili ko] sa ganyang gawain hanggang pwede pa.

(So as long as I’m alive and able, I will offer myself to this line of work.)

There is a prayer attributed to…St. Oscar Romero…He was killed while he was speaking out against the dictatorship in El Salvador in the 80s. The prayer [had a line like], “We are prophets of a future not our own.” That, to me, is the spirit behind what I hope to be able to [do]. It speaks about the work of a pilgrim on Earth, having the humility to accept that our work will never be done, or fully accomplished.

Imparting a lesson he wishes for the youth to keep in mind, Gascon also discusses the metaphor of “pounding the rock”. In the form of a story, the metaphor is based on a stonecutter who goes to the mountain quarry on a daily basis to do his work. The late CHR chair explains that while the stonecutter will not be the builder of the bridges, highways, mansions, and palaces that the raw material will be used for, they keep working. He kept pounding the rock.

“Rock is very hard to break…he does not know when the rock will break. But he just keeps pounding,” he points out. “That’s all we have to do [as well]. We just keep pounding it, because we have hope. We trust that it will break…So we’d persevere. And then it will break.”

Gascon furthers that the moment the rock breaks, it is not the final strike that finishes the job but every single strike done by the stonecutter. “Even in our darkest moments, when we thought that we should end and stop…we [shouldn’t],” he finishes.

Much like what Gascon reminds us, we just have to keep pounding the rock, to do the best we can with what we have.

“If it is not enough today, [you] wake up the next day and keep doing it until it will be enough.”

Gascon previously taught in the University until 2014. Last October 9, Saturday, he passed away due to COVID-19 at 57 years old. And as he promised himself, he kept pounding the rock until his very last breath.

With interviews from Jan Emmanuel Alonzo

This interview was edited for length and clarity.