Apologizing has been observed since the dawn of human language; making amends to mistakes is very human after all. But as political norms and sensitivities to certain issues continuously shift to create a more inclusive and politically correct society, apologies have repeatedly been overused, sometimes even misused. From genuine reconciliation to calculated performances, apologies reflect the values a community holds, hoping that the people living in it would become catalysts for social change.

A good apology

We all know that apologies are a common ritual, a polite act of social nicety to achieve empathy and to reconcile. It can be an avenue for healing that acknowledges the hurt that someone caused another. Sadly, it can get difficult to construct one because of excessive pride or a fear of the consequences that comes with it.

A Vox Explained documentary on apologizing listed seven essential steps in reconciliation: vocally expressing remorse, validating a person’s emotions over the mistake, taking responsibility, suggesting an explanation, making a proposal of repair, committing to change, and requesting for forgiveness. However, they mentioned that at least three of these steps are enough for an apology to be effective.

But not everyone requires an apology to heal—some choose vengeful paths, some use it as fuel for productivity, and some resort to escapism to completely suppress the hurt. All the ways to heal depend on the path that feels right for the victim, but what these methods have in common is the agency serving to empower the afflicted by taking control over their own narrative. The opposite of trauma isn’t healing after all—it is power.

Sorry not sorry

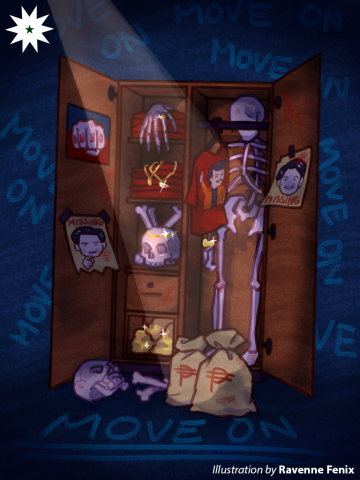

In the country, people crave for pointing out the faults in prominent personalities—or any public figure. This incites a witch hunt to reveal the forgotten skeletons in people’s closets. This consistent saturation of apologies leads to normative dilution that could lead to apologies sounding unappealing and disingenuous, making it more of a performance than an authentic act of empathy.

Like any other form of change, forgiveness is difficult to undertake. It requires lowering one’s pride and admitting imperfections. Opening oneself to vulnerabilities could make people fear the unexpected and the overwhelming price of change. The progress toward materializing repentance is long and arduous to the point where some cannot even endure it; old habits die hard with a closed mind. Hence, a lot of people prefer to turn a blind eye on the truth in order to escape the pins and needles of accountability.

This is most blatant when encountering political apologists. In history, they are no stranger to controversy after all. As early apologists weaponized religion in court, Christianity was often used as a scapegoat in committing crimes—as the divine’s forgiveness is all-encompassing no matter what. And the Philippines is no stranger to this subjugation—with the infamous God, Gold, and Glory conquest of Europe.

The reckoning

For those unable to recognize their faults, cancel culture steps into the picture, crucifying enablers without changing the environments that cultivate their behavior. Thus, canceling is more of a warning to be careful rather than a demand for change—which makes it important to look at the matrix of things in order to break the cycle of trauma.

For example, neocolonialism ravages impoverished countries and communities that shackle them in a course of injustice after centuries worth of looting and imperialism. Those without power have been exploited to enable all kinds of hate, may it be by a person’s class, gender, or race. Meanwhile, those in power would internalize habits that normalize and institutionalize tyrannical behavior.

With the recent uproar of the Black Lives Matter movement, it shows that the hurt from systemic injustice does not heal by forgetting or ignoring, but with stern perseverance that starts with proliferating agency. Defacing and amputating statues of colonial masters by people of color was a pivot in history, manifesting collective action in reclaiming the lost narratives of their people.

Closer to home, the Philippines’ semifeudal structure favors the ruling class, as seen in the heavy militarization of Lumad lands, the COVID-19 pandemic response, and the war on drugs. These violent operations that cultivate fear for discipline subjugate the Filipino people to obey its oligarchs or suffer the brutal consequences. As the country is inherently rich agriculturally, farmers who sow the land and fisherfolk who reap our seas are marred from their rights and even silenced forever in search of justice.

We don’t even have to look far back in time to see parallels that can prevent casualties. But what use are folklores of aswangs when the boogeyman is right under the people’s noses—complacent with the accruing smell of oppression, they are numb in the sense. Even in their own demise, they can’t perceive its stench.

How sorry are you?

As the country faces another crucial time in history with the 2022 elections, the race to power has been reopened by democracy. Blind faith can be a threat in perpetuating false narratives that prevent the country from healing. Forgotten by the minds that brush off past horrors, it is important to remember the memories of those with unmarked graves and validate the traumatic experiences that the people have suffered from.

May it be interpersonal mistakes or collective discrimination, an apology cannot revive the dead nor take back time’s cruel actions. It is very heavy and sobering to continuously fight for accountability and change in order to move forward. But there are those who live and die fighting a noble cause to dismantle and deconstruct unjust systems. As Desmond Tutu once famously said: ”If you are neutral in situations of injustice, you have chosen the side of the oppressor.”