The Philippines boasts of literature that casts from language and culture. For Dan Ong (II, CRW-BSA), he believes, “[Folktales] fulfill cultural and spiritual needs, modified to suit the [demands] of people according to the times.” This is most apparent in Visayan folktales, especially those written in Hiligaynon, doubling as a channel of entertainment and hurubaton or proverbs for the ancient Visayans.

What harmonizes the essence of Philippine folktales is the versatility of women’s roles within these stories. It reflects how the native world allowed women to be free from the chains of sexism and misogyny. Such societal constructs paved the way to empower precolonial women toward self-expression. Above all, women telling these narratives were construed as influential, with a keen sense of wisdom which progresses the flow of these tales.

Behold her power

The common notion about women in Philippine folktales is that they are confined to a domestic standard. For instance, the famed tale Malakas and Maganda delineates women as merely beautiful and frail human beings. But Early Sol Gadong, vice president of Hubon Manunulat—an organization of writers from Western Visayas—clarifies, “[Hiligaynon] folktales contained stock characters. So, may mga typecast roles [especially for women].”

(They include typecast roles especially for women.)

In Mansumandig, it is the wife who manages and safeguards the family’s finances; meanwhile, seven disobedient daughters are turned into seven islands in Siete Pecados. A woman can also be portrayed as a warrior, such as in Hinilawod, or even the moon who courageously deserts her abusive husband—the sun—like in Ang Ginhalinan Sang Adlaw Kag Gab-i.

The customs of these tales show an egalitarian relationship between men and women. It is evident in the tales of the sun and moon where Gadong stresses that these women should not be inferior to men, “In Hiligaynon [folktales], hindi pwede daog-daogun sang husband ang wife.” As such, women in these tales have the freedom to respond to the clamor of self-actualization and practice their agency.

(Husbands can’t just subjugate their wives.)

These stories paint many diverse pictures of women’s strength—damsels who are unafraid to exercise their power. The roles these women portray thus can become inspirations for girls who may read these stories, encouraging them that they can be as equally fearless and powerful. “In a way, the folktales are mirrors of society. Kinukuwento niya kung ano ‘yung societal context of that time,” Gadong furthers. Although Spanish colonization molded female characters to fit the Virgin Mary typecast—obedient, pious, self-sacrificing, and uninterested in vanity—Gadong believes powerful portrayals from precolonial society were still able to “seep through the cracks of…the image of Catholic women.”

(They tell of the societal context of that time.)

Beyond the stories

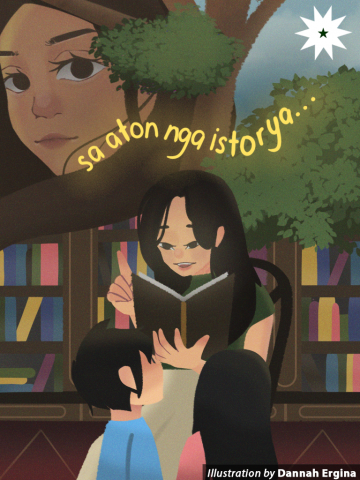

These empowered interpretations of female characters are largely thanks to the women’s roles as storytellers. “They are the ones who are mostly telling the story, and whoever tells the story…dictates how the story runs,” Gadong explains.

She further points out that when men tell folktales, their leads exude overly-macho traits. “[These stories have male characters] who are [merely] cunning and street-smart, [thus], are able to win [girls over].” This is evident in the folktale of Juan Pusong, Western Visayas’ own Juan Tamad. “I have a feeling na kapag lalaki ang nagkwento, kahit na nagloko or naging tuso si Juan Pusong, he [still would win] the girl.”

(I have a feeling if men tell this story, even if Juan Pusong is cheeky or overly cunning, he wins the girl.)

In contrast, “Kapag nanay iyong nagkuwento…always ine-emphasize na dahil sa katamaran [niya]…hindi siya umasenso,” she furthers.

(If mothers tell that story, they emphasize that he doesn’t succeed because of his laziness.)

But if the women were “putting us in our place” back then, Gadong inquires, “Bakit ngayon…napakamarginalized ng boses ng babae?” She implores for us to take a look at how society frequently overlooks women, both in real life and in fiction, where the important contributions of female characters are downplayed.

(Nowadays, why is it that the voices of women are marginalized?)

“While we give so much value [to] men in stories…baka kailangan natin i-reframe ‘yung pagtingin natin sa [mga] ito,” she continues. “If [it weren’t] for the constant guidance…of mothers [and] grandmothers, mapapariwara ‘yung bata.” Truly, within and beyond these tales, women held revered roles that influenced their communities, and thus deserve to be more recognized.

(Maybe we need to reframe how we view these stories. If it weren’t for the constant guidance of mothers and grandmothers, these kids would be lost and reckless.)

Newly forged paths

The inherent value of these folktales justifies how the country must preserve its legacy. One way to start is to call for more faithful translations of such impactful literature. One scenario Gadong imagines is a straightforward translation from one local language to another. “For example…from Hiligaynon to Kapampangan [or] from Cebuano-Bisaya to Blaan. So pwede naman ganoon—diretso,” she mentions. This initiative would greatly benefit those whose first or second language is not Filipino, just like Gadong, “I [speak] Hiligaynon but I can understand and write in Kinaray-a better than Filipino.”

(So it can be a direct translation instead.)

She further illuminates that the country’s education system should do more in making these folktales more palatable to students, either by simplifying the story or adapting it to modern tastes. In Gadong’s colorful Si Bulan, Si Adlaw, kag si Estrelya, she portrays how the female Moon and her children—the stars—escape from the clutches of the husband and father, the Sun. “So here, we have a woman who is independent enough and brave enough to leave an abusive husband,” she notes, inspiring people to stand up and defend for themselves.

While accessibility of these folktales has improved due to online resources, as well as the collective efforts of various individuals throughout the country, they need to be supported by systemic change. “Bakit hindi pwedeng gumawa ng batas where subsidized iyong pag-create ng libro tungkol sa folktales [o] na dapat iyong mga pinapalabas sa TV, 10 percent based on folktales?” Gadong imagines.

(Why not create laws that subsize folktale books or enforce that at least 10 percent of the shows on television are based on folktales?)

Harmony in diversity

Losing precious pieces of history can only further complicate the more recent issues of today. Much of the prized values that these women storytellers emphasize promotes solidarity and good virtues. “A lot of the problems of Filipinos stem from the fact that we focus too much on our differences rather than [on] our similarities,” Gadong expresses, claiming that understanding the varying aspects of our country’s culture would lead to appreciation from all.

In fact, most of the folktales focus on the importance of fostering the community or the self; these took precedence over regional identities, which remains true for contemporary stories targeted toward Filipino children. As Ong proposes, “It is equally likely that certain folktales are shared between cultures, perhaps altered to better suit the individual context of these social groups.”

After all, folktales, whether Hiligaynon or otherwise, are crucial tools for better understanding the world that our ancestors lived before, and the current one around us. “Bearing witness to our cultural diversity allows it to endure just that much longer instead of remaining ignorant to its beauty,” Ong aptly imparts.