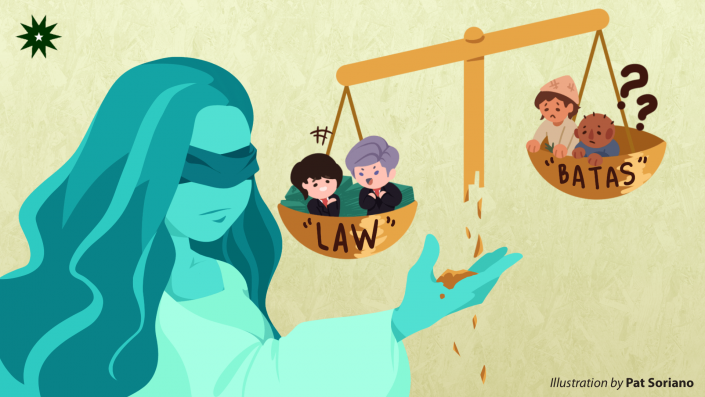

They say that justice spares no one; every man and woman, rich and poor, is laid out the same in the eyes of the law.

But Atty. Mariko Iwaki, appointed lawyer at the Public Attorney’s Office – Dasmariñas, explains that challenges are inevitable in judicial assistance, especially the language barrier. The Constitution cites both Filipino and English as the official languages used for communication and instruction. However, most official documents are still written in English, leaving those who are not fluent in it with difficulties navigating through legal procedures.

“Merong mga [clients na] nagpapa-advice samin, hindi para ikwento ‘yung problema nila, but to show me the order and [to] let me interpret it for them,” Iwaki laments.

(There are clients that come in for advice, not to consult about their problem…)

Though Filipino lawyers mostly converse with clients through the local language, the Philippine court conducts all proceedings in English. This places non-English speaking clients and witnesses at an automatic handicap. “If you will file a case, you will need a good lawyer who speaks English well to do the pleading for you,” states Dr. David San Juan, full professor from the University’s Departamento ng Filipino. “If the justice system, our laws, and court decisions are all written in English, etsapwera ang mga hindi [nakakapagsalita] ng English.”

(Those who can’t speak English are left out.)

Ignorance of the law excuses no one. But if it is written in a language that disadvantages a large portion of the population, the Philippine justice system has become shaped with a gross oversight.

Remnants of the past

Although it’s been decades since the nation attained independence from American rule, the prolonged period of foreign occupation meanders in present society. San Juan imparts, “If the current education system is managed by people who favor the colonial education system…we can argue that colonialism never left our land,” citing the hegemony of English. Matthew Garcia (I, PHM-BSA) shares San Juan’s observation; in subjects like economics, he finds the approach focused on the Western context.

The Department of Education’s Mother Tongue-Based Multilingual Education Policy is one of the government’s initiatives to bolster Filipino and local languages in the education system, but it’s far from perfect. Garcia shares his own experience with the policy in elementary, which helped him understand the Filipino language better. He says this also helped other students be more confident in the subjects, as they can easily understand the lessons. However, he cites, “Come fifth grade, the shift from using Filipino in our subjects to English was much easier for me, but I noticed that it was much harder for everyone else [who] wasn’t great at English.”

And while the Freedom of Information Bill (FOI) asks government agencies to translate key national information into major Filipino languages, the Congress has yet to fully pass it into law. “Aside from making laws [and] executing them, communication is the key. How can you deliver a message if the receiver cannot understand it [in the first place]?” Iwaki posits. Because of FOI’s inadequate implementation, she notes that only a few municipalities and cities have translations of their policies to date.

Mind the gap

English cements itself as a device that divides society and widens the gap between the powerful and the poor. San Juan observes that legislators will often overlook and rarely listen to appeals written in Filipino. “Pero ‘pag nakasulat sa Ingles ‘yung appeal, makikinig sila,” he points out. For a country that prides itself on having bilingual citizens, our own language is severely neglected in professional settings.

(But if the appeal is written in English, they will listen.)

Thus, the plight creates room for miscommunication in legal procedures. Iwaki recounts a case where a detainee was supposed to be released months before their visit, “When [a detainee] receives an order from the court, titignan lang nila [at iisipin], ‘Pangalan ko na ba ‘yung nandiyan?’” Sadly, the detainee stayed much longer than what was required because they couldn’t understand what was written on the court order. “[Hindi nila alam] ‘yung mismong contents ng order [kung] anong nangyari [o] kung anong gusto ni judge,” she deplores.

(They’ll just look at it and think, ‘Is it my name that’s written there?’. But they don’t know the contents of the order itself, what happened to the proceeding, or what the judge wants.)

Cases like these render a Filipino who doesn’t understand English to be disenfranchised in their search for justice. San Juan claims that, before anything else, changes need to be made at the grassroots level of the education system first. The road to intellectualizing the Filipino language is long and winding, but it isn’t a hopeless one.

For Filipino to be used more widely across all professions, educational institutions will have to “walk the talk”, as the professor puts it. “As long as the teachers have the capability, allow them to teach in Filipino. Encourage undergraduate and graduate students to use Filipino in their thesis or dissertations,” he provides.

In it for the long haul

“The orders and procedures in court are already hard to understand on its own,” Iwaki conveys, “so kung mapapaintindi sa kanila sa paraan na mas naiintindihan [nila]…hindi na sila clueless [as to what is happening].” Carrying out court procedures in Filipino and other local languages would also speed up the process, no longer requiring a court interpreter to speak for the witness or their representing lawyer.

(If court orders and procedures will be conveyed in a way that people can understand them more, then that’s all the better. They will no longer be clueless as to what is happening.)

This is not just a matter of understanding the law that governs the nation, but being able to exercise the rights afforded to the citizens. “Hindi matatakot ‘yung witness magsalita…Mas maitatanggol niya ang kanyang sarili [at] mas maipapahayag niya ang ano gusto niyang sabihin,” San Juan claims. Similarly, Garcia adds that promoting the use of a local’s mother tongue in court can be “empowering and [it gives] opportunities” for people who are more comfortable with their language. By allowing involved parties to speak freely in the language of their choosing, the law already better upholds the impartiality it swears by.

(The witness will not be afraid to speak. They can defend themselves properly and they can better convey what they want to say.)

Ignorance is only bliss for those who wish to abuse it. When the Filipino languages are used on a national scale in fully translating legislation, there would be no room for miscarriage of justice. Everybody can be on the same page at the same time, as everyone should be.

As we shape our tomorrow, we must remember that a future that is bright and full of potential is useless if only a select few can bask in its brilliance.