“Kapag natalo si Leni, I can’t wait to log in to Twitter to see [those] beautiful kakampinks’ tears,” a tweet reads.

(When Leni loses…)

This quote is the spirit of schadenfreude, one of the most tactless parts of the spectrum of human emotion. Owing its etymology to the German nouns schaden and freude—which means damage and joy, respectively—the term classically encapsulates the hidden delight one gains upon beholding or simply imagining the misfortune of an adversary. German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche articulates it best: “To see others suffer does one good.”

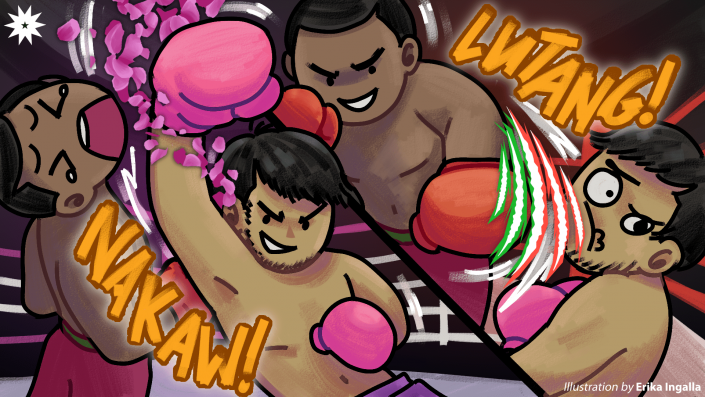

When compared to the sprawling Bible verses which egg on its readers to forgive their transgressors, engaging in schadenfreude is a much easier route. A boxing arena of its own, schadenfreude manifests as a sly smile, a shared piece of gossip, and a surreptitious bout of pleasure. Yet, as far as schadenfreude seemingly satisfies one’s sense of justice, it often causes more problems than it solves.

Buti nga sa’yo

Schadenfreude unconsciously seeps into the fabric of daily communication. As a commentary by The Manila Times notes, schadenfreude is primarily fueled by ego.

Thus, we may see the opposing side as wicked, where their misfortune becomes a form of karmic justice. We howled with joy when Eleven punched Angela in the fourth season of Stranger Things; we boisterously cheered when Thanos turned to dust at the end of Avengers: Endgame. This form of retribution is what undoubtedly sends a rush of adrenaline to one’s brain, while experiencing satisfaction as the villainous opposition suffers. In the words of Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker, “They get what they [expletive] deserve.”

However, schadenfreude becomes more sinister in a political context, especially in the Philippines. Many Filipinos exhibited it when former President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo was found to have rigged the 2004 elections. While many justifiably called out Arroyo’s actions, pettiness easily diluted the discourse. Instead of addressing the issue, many Filipinos simply mocked her distinct voice, which was ripe for caricature and sketches. This later evolved into ironic ringtones to the tune of Arroyo’s infamous line, “Hello, Garci”—which became one of the most popular quotes in the world at that time.

Subsequently, the deluge of vitriolic, politically driven social media posts became schadenfreude’s crowning glory. Anonymity gave individuals the courage to voice out polarizing opinions without facing its repercussions. Fake news and unjustified speculation have started spreading in echo chambers. For instance, former President Rodrigo Duterte’s detractors showed enjoyment amid rumors of his declining health in early 2021. When he responded to his detractors during a speech last April 12, Duterte and his supporters claimed that these rumors were from political rivals who want to see the then-president dead. Unsurprisingly, this toxic back-and-forth affair ultimately steered the focus away from more important issues at the time—the fiscal policies to control the deadly spread of SARS-CoV-2.

Going nowhere

On top of the ever-growing propensity for schadenfreude in political discourse stood the ultimate battleground: the 2022 National and Local Elections. What the supporters of then-presidential aspirant Ferdinand Marcos Jr. and former Vice President Leni Robredo lacked in ideological similarity was made up for by their shared will to smear each other. Indeed, the perfect environment for schadenfreude was created by the steep polarization and faceless social media algorithms that were woven years before this intense election.

It comes as no surprise that the Marcos Jr. camp deliberately began the schadenfreude campaign against Robredo. A copious amount of disinformation regarding the supposed pitfalls of Robredo’s governance as a vice president was readily disseminated by the Marcos Jr. team through social media. While Robredo constantly preached her “radikal na pagmamahal” platform in response, her supporters descended into animosity by celebrating reported robberies during a UniTeam rally and Marcos Jr.’s SARS-CoV-2 diagnosis.

(Radical love.)

This era of schadenfreude reached its climax once the elections concluded. Marcos Jr. followers considered it a personal victory that Robredo lost the election—finally were they crowned the winners of the fight for schadenfreude. But with the kakampinks’ lament for Robredo’s defeat, their sincere wish for the country to fail under the new administration grew as well. News of national blunders were seen as laughingstocks for Robredo supporters; never mind that they, too, were just as affected by them.

Although the kakampinks’ ideological anger for the opposite side was certainly defensible, the route to where this wrath went was sorely misdirected to petty, trifling matters. Feeding the fire, devotees on both sides of the spectrum focused their energies on a childish ideal; instead of the election being issue-based, it centralized on assailing personalities and tribes. On all fronts, schadenfreude was a victim of its own success—harrowingly proving that it did more harm than good.

False gods

With no signs of stopping, schadenfreude is still apparent in many aspects of social discourse. After all, it is like a drug—temptation is sweet, but satisfaction is fleeting. The instant win of an ego boost reflects the contradictions in human nature.

Robredo’s supporters claim to be champions of her humanitarian efforts but subsequently decline aid from those who have not voted for their candidate. On the other side of party lines, Marcos Jr. is seen repeatedly giving lip service to unity, while his supporters are main agents in the polarizing political climate. How unbecoming is it of supposed principled individuals to let go of their values in exchange for seeing others’ misfortunes?

Ultimately, we are mere victims of the idolatrous nature of Philippine politics. The hypocrisy in its partisan nature is deeply engraved in how we perceive it. In a country divided, we are forced to demonize one another, nipping genuine collective action in the bud before it even has the chance to thrive. Unlike the strong will they displayed when they ousted the late dictator as they marched in EDSA 36 years ago, Filipinos have forgotten to stand behind political ideals as opposed to solely idolizing politicians.

As the potent schadenfreude among many Filipinos shows us, unity is still far from arm’s reach. In the end, we are all on the same boat. We can choose to all sink into an ocean of crises, or to stay afloat and to prosper together.