Life will always ask the questions, while death gives the answers. Witnessing your loved one wrestle their life away brings a variety of emotions and reactions that fill your mind. It makes you wonder if there could be any other possible ending to this nightmare one cannot wake up from.

But the result almost always remains the same.

We dress in black as a sign of mourning and offer our condolences before saying our final goodbyes. The departed is surrounded by white flowers, family, and friends. The burning candles remind the mourners that each light would eventually burn out. One by one, the items on the list for mourning are prepared, but nothing can fix the space those who pass leave behind.

Family dinners with a missing chair, a cold bed, an uncomfortable distance between the pictures framed against the wall—these empty holes in our lives, once filled by someone important, serve as a reminder that everyone, including the ones we love, are living on borrowed time.

Death has no conscience

At times, there can be too much of everything. Vivid memories can become overwhelming, almost shackling. Those left are consumed with the thought of the departed, “the laugh, the voice—was it a notch higher or lower?” Details come to mind: The eyes, the gestures, the habits, the favorite outfit, song, or color; a gift, a place, a car ride, an event unforgettable, something borrowed that was never returned.

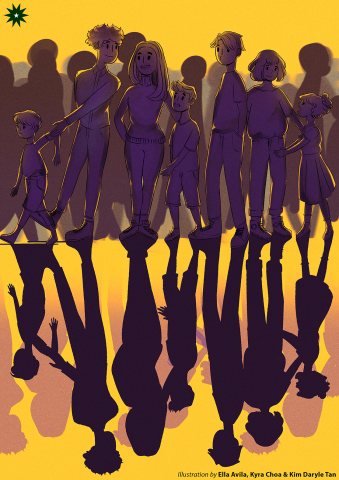

The expanse between the living, breathing world and that of the dead can often manifest as a battleground. The loss of life carves a gap that the bereaved attempt to cross, looking for answers or some form of explanation. There emerges a tendency to sow comforting thoughts about the deceased being in a better place, fulfilling one’s life mission, or time and destiny conspiring that it was simply that person’s turn to go. The living are left to search for meaning and purpose in every nuance.

“I really should have seen it coming. My rosary snapped when I held it lightly to pray for my aunt’s recovery. It was probably a sign,” Brendan* narrates the moments before his aunt’s passing on the hospital bed.

Mourning takes on various forms for different people. The extent of suffering and grief range from peripheral shock and pity to more pronounced anguish—akin to a distress signal that never ceases or a traumatic response that recurs and suffocates like a pressing storm.

Brendan shares, “The rosary incident [was] very traumatizing, especially because I had full belief that God will listen to me at a time of need…it’s [an] event I don’t want to return to.”

As heavy as the word may seem, “trauma” has in fact been associated with death, or rather, the void it leaves behind. Psychological research recognizes worsened mental health and degraded life satisfaction in the bereaved, with a recent study finding that a friend’s death can be just as emotionally devastating as that of a family member. Such is the nature and power of attachment.

One life, for the two of us

Patrisha Magcanan, a 19-year-old student, recounts the nightmarish moment she discovered her father died in a sandstorm abroad. “It was in 2005 when my father gave us a call. I asked him multiple times about his leave from Saudi Arabia. He told me he’d come back soon, and he promised to come back. Indeed, not so long after, he came back as a corpse.”

Being six years old at the time, her response was confusion. All the scenes—from the arrival of the corpse to the funeral—were faint images for her. Yet day after day of not seeing her father, of losing their market strolls, missing his kisses on her forehead, of no longer hearing his voice over phone calls—reality sunk in.

“His death’s not entirely about losing a father; I lost the greatest friend I had,” Patrisha further expresses.

As a kid who “got separated” from her best friend, Patrisha looked for ways to fill the spaces left behind—creating days where she could remember him, talk to him, be with him. She would write letters to her father, narrating how her days went and casually talking to him as though he were still alive. It had become her form of meditation until now, a remedial therapy to the pain she said she couldn’t get away from.

The inevitability of oblivion is what makes us human. Often, we try to compensate for our limited time by leaving traces of ourselves everywhere we go. These vestiges etch out the space that the deceased leave behind, making the bereaved not only seek out the dead’s presence but also fear for their own mortal nature, their own life—actions, achievements, identity—fading in the stretch of history.

“We’re scared to be forgotten, and we fear that we might die unsatisfied…Embracing death might help us understand this crazy world—and still become happy,” Patrisha reflects on accepting the inevitable.

Affirming life

Learning to live with loss, however, requires more than patchwork fixes and cover-ups.

Brendan and Patrisha had individual means of coming to terms with the tragedy, but both discovered that a kind of social grieving offered a less numbing and more consoling way to cope. They realized they were “not alone” in suffering, as Brandon puts it, collectively finding “healing” with other family members who understood and were experiencing the same agony.

In her father’s absence, Patrisha felt the presence of someone who had been bearing the same pain, while still being strong for her and the rest of their family—her mother. Patrisha promised to herself to acknowledge the struggles of those people around her who carried the same afflictions, and to be a source of strength, especially for her now-widowed mother.

Recognizing the reality of affliction and the continuity of life after someone’s passing, Patrisha acknowledges, “The pain can’t vanish easily, or I think it won’t vanish. But I’m sure that it’s not as painful as before.”

The space between the bereaved and the deceased can be intimidating, crushing, and hollow on the worst days. Like the pain, the healing too can come in spurts when we don’t deprive ourselves of the chance to grieve and to be upset—fully, without remorse, with the intensity of agitation and hurt—to feel all these, and to be human.

Perhaps we start off feeling left behind, singled out by an unfortunate twist of fate. But gradually validation, courage, and strength can emerge as we keep ourselves involved with good company, engaged with the free flow of life.