The Philippines is slowly crawling toward the 2022 national elections. Yet that doesn’t necessarily mean that we are more than prepared. Ranking last in the Nikkei Asia COVID-19 Recovery Index, the people are clear to let the next leaders of our country know that it’s time to get the work done. But it’s imperative for people to know which candidates should be put in charge of it.

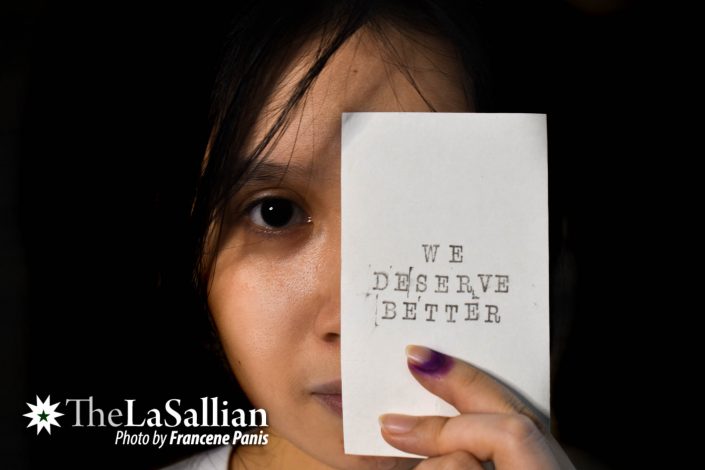

However, we’ve seen this time and time again. Frustrated citizens select a candidate who pretentiously promises change—only to fall back into the chasms of corruption, injustice, and poverty. This system goes on in circles; thus, we never really learn from falling for the strategic system that lures us with grandiose promises. Still, that doesn’t stop advocates from letting the masses know how to vote smarter and wiser.

No calm before the storm

Politically charged arguments on social media can be clear indicators that the national elections are on the horizon. Among these arguments lie a singular, often overused insult: bobotante. While the regular Filipino netizen may be desensitized to the contemptuous remark, its very existence calls into question its validity and most of all, its substance.

To Cleve Arguelles, an assistant prof. lecturer from the Department of Political Science and Development Studies, bobotante bears no merit in its form or usage. He stresses that it only serves to alienate the voters from one another, where “it shames them and maligns them just because they’re voting the other way.”

Genevieve Giron (II, BS BIO-MED), a first-time registered voter in the upcoming elections, echoes the sentiment by calling the term “inappropriate and derogatory.” Although she recognizes that some voters choose to stay ignorant of the political atmosphere, there is no sufficient rhyme or reason for calling someone a bobotante. “It is usually used to shoot down voters who vote for what the collective population [deems] as ‘unqualified’ candidates,” she stresses.

Arguelles emphasizes that characterizing voters as a bobotante for choosing the opposing candidate or party is no longer democratic in a system where the citizens’ votes should be fair. “It’s [our] motivations, our desires, and our interests [that drive the reason] we vote for certain candidates—it’s equally valid as others’ [own reasons],” he expounds.

In fact, there is a myriad of factors that shape one’s motivations behind voting. Some might conduct extended research on a candidate’s platforms; others may simply observe if the candidate is able to extend basic services to local communities. Arguelles asserts that although these justifications may belong to quite different ends of the spectrum, both are nonetheless valid. “I think the challenge when we say that other voters are bobotante is that it shuts down the conversation instead of enriching it in terms of why other people vote that way,” he reasons.

Nakaligo ka na ba sa dagat ng basura?

But for the most part, the people would look at a different quality for their chosen leaders: fame. This is further emphasized by their political campaign starter pack: a catchy campaign jingle, a charismatic personality, excessive publicity materials, and most importantly, a familiar surname.

Arguelles cites that the absence of strong institutionalized political parties in the country is why Filipinos have the tendency to vote based on personality. “For people to consider you as their candidate, kailangan kilala ka nila,” he suggests. Thus, he believes that people “reduce the cost of making an informed vote” by only focusing on their names, their taglines, and their jingles as information shortcuts.

(For people to consider you as their candidate, you have to be memorable.)

Privilege and elitism also play a huge role in voting decisions. “In many communities of poor voters, the question that they would usually ask is, ‘Sino bang nakapagpadala ng services and goods in this community?’” Arguelles mentions. When it comes to other aspects, however, it becomes a different story. “They couldn’t afford to vote on the basis of principles or programs…because they don’t have the privilege of doing that, especially if the government isn’t well-placed in providing these services to all of its citizens.”

(In many communities of poor voters, the question that they would usually ask is, “Who gives services and goods in this community?”)

Giron conveys that she values candidates who are willing to speak up for those who cannot. A person in government must be able to “lead, serve, and fight not only for the people, but with the Filipino people.” Meanwhile, Denise Li (II, BS BIO-MED) is quick to remind candidates that they must not run to achieve power, but instead “to work for the people.”

Problems in our solution

While voter’s education is built with good intentions, it is time to question its effectiveness—or rather, its impact on the overall electoral initiatives. Perhaps the solution is also part of the problem.

Arguelles argues that there is a neglected issue of “over-focusing on voter’s education and centralizing all our resources and energies on that.” He explains that it potentially loses sight of what plagues elections. “The problem is that [voter’s education] does not recognize the problems in our electoral system design.” Further, he mentions that educating voters becomes more strenuous because the country’s electoral systems aren’t favorable to the democratic nature that voting should inherently have.

Instead of pinning the blame on voters, “We have to shift the burden on the Comelec (Commission on Elections) and other election authorities,” Arguelles asserts. He suggests that improvements must be made on the elections themselves; if an outdated system only comforts the powerful, it is evident which sector is favored and which is undermined.

For example, he clamors for the regulation of online campaigns, which is further burdened by rampant disinformation online. Without proper control, “it’s becoming more innovative and sophisticated in every election cycle.”

Consequently, access to improper information channels becomes part of the problem. Despite being well-versed in technology, Li herself admits, “Super dali ako madala ng fake news.” This burden is even heavier on voters who suffer from the digital divide—lacking gadgets and digital skills—while also being unfamiliar with digesting information online.

(It is very easy for me to be swayed by fake news.)

It goes without saying that stepping into the minefield that is politics is not for everyone. It requires a certain level of grit and steel for a person to be competent in understanding these political systems. But if reliance on personality is the sole factor for choosing our heads of state, it could bring the nation into a downward spiral.

In the end, every citizen must remind themselves that they are choosing a candidate who is saddled with the responsibility of carrying the country on their backs. One vote can change the tides toward a better system, and then perhaps a better future.